In February of 2006, I got a call from a man who wanted to book a trail ride. He was old. I could tell from his voice. I was nervous. Even in a best case scenario, taking brand new riders up into the mountains on horses in good weight (i.e. not half-dead deadheads) is an anxiety-producing endeavor. A brand new rider who is also elderly is not a best case scenario.

Mr. Millman and his wife showed up later that week, confirming my worst fears. He was elderly, he was frail, he looked like he’d break into a million pieces if he fell. I prayed Scout and Lady would be on their best behavior, and they answered my prayers. That day he told me he’d ridden some a few decades ago, and since then it had been his dream to own a horse.

Many people believe that horses are like unicorns. They’re not. They are a catastrophe waiting to happen. If you wait long enough around a horse, you will witness a catastrophe. But horses produce more than catastrophes, they also inspire love, and hope, and joy. Mr. Millman wanted himself some of that.

After he had a couple of rough rides on Scout, and stayed resolute in his desire for a horse, I introduced him to Colonel, a Quarter Horse gelding I’d had my eye on for some time. The very day Mr. Millman tried out Colonel Mrs. Millman gave me some news – Mr. Millman had been diagnosed with cancer. It was serious. The thing was, Mr. Millman didn’t have time for cancer. He had a horse to buy, a skill to learn, a life to live.

I should have known it wasn’t destined to work out with Colonel when we discovered the horse had a swastika brand on his hip. What are the odds that a horse with a swastika brand would be purchased by a Jewish man in South Carolina who was of age in WWII? We rebranded Colonel to obscure the swastika and got to work. Unfortunately, Mr. Millman made the horse nervous. I loved Colonel, found him to be a wonderful horse, but that didn’t mean he couldn’t produce a catastrophe. He was a horse, after all, and along with love, hope, and joy, catastrophes were his stock in trade.

Mr. Millman’s sister had come visiting, and Mr. Millman being Mr. Millman, he wanted to show off his new horse. I looked into Colonel’s eye that day and saw bad things. He was anxious, and shied as Mr. Millman dismounted. Mr. Millman stumbled backward, tripped over the mounting block, fell to the arena sand, hit the back of his head and lost his memory. He didn’t know who Colonel was, he didn’t know what had happened, he didn’t know his address. It’s never a good day at the barn when your rider leaves in an ambulance.

I found Colonel a new home, and cried when he left. Years later, I would see him at a horse show, looking fat, healthy and happy, and cried again.

I felt certain Mr. Millman would abandon his quest to become a rider.

He didn’t even take a break.

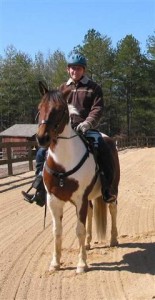

Shortly after the catastrophe, he called me up to Chesnee, to come see a Missouri Fox Trotter for sale. I looked into the Trotter’s eye and saw something I didn’t like. A hardness. Mr. Millman passed on the horse. A few days later, he summoned me back to Chesnee. The Fox Trotter farm had a new horse in, a horse named Sam. I made the drive to see the new prospect. He was coppery red and awfully young. I looked into Sam’s eye, and saw goodness reflected back at me. I rode him. He had a fire to him that matched his blazing coat. Sam was alert, responsive, ready to do whatever you asked. He was sensitive. But the look in his eye told me it would be okay. Sam arrived at the equestrian center and once again, we got back to work. There were many obstacles. Sam was young and green, Mr. Millman was old and green, but they were both hard triers. Slowly but surely, their partnership grew.

At the same time, I found a new horse for Mrs. Millman. Johnny was sold as a Quarter Horse cross, but I didn’t see the Quarter Horse as much as I saw the draft. Johnny was nothing like Sam. His eye did not reflect back pure goodness, but rather a most healthy sense of self. No one had ever told Johnny he had a giant hammerhead, or that his back was as long as a drive through Texas. But even if they had, Johnny wouldn’t have listened. He knew the truth – he was one glorious hunk of horseflesh. As such, he was entitled to his opinions. Some people he didn’t like, others he loved. Thankfully, he loved Mrs. Millman, and toted her around with a smile on his face.

Mr. Millman’s cancer advanced through his body, even as he perfected his riding skills and his partnership with Sam. I left the equestrian center, and left Millman duty to my friend Melissa, who would take Mr. Millman and Sam on two hour trail rides over hill and dale. Sometimes, when he felt poorly, Mr. Millman would list in the saddle. Sam would find a way to get back underneath him. With sweet, young Sam, no catastrophe lay in wait. Only love, hope, and joy.

Mr. Millman had lived his dream. He owned a horse and had learned to ride. But Mr. Millman wasn’t done dreaming yet. He wanted to own his own farm. He’d expressed this desire early on, and I, stupidly, had dismissed it as too far fetched. By 2008, Mr. Millman had moved to Charlotte and built his two geldings a magnificent barn to call their home. He had done it all. Through the years we stayed in touch. I kept up with Mr. Millman’s equine adventures, and was saddened by the news that Mrs. Millman had left. I sent holiday cards and emails, and made sure Mr. Millman knew I was always there if he needed me.

In 2006, Mr. Millman and I had obliquely discussed it. I don’t know if it was ever named, and doubt that it was. I think it was more a matter of knowing looks and a nod of the head. But there was an agreement between us, and it was an agreement I knew would stick. And so, I waited for the call.

I got it on October 27th.

Mr. Millman was dying, and he needed to find a home for Sam and Johnny. He had one condition – Sam and Johnny must stay together. I wrote up an email and sent it out, knowing it would find the right person. The email was forwarded, forwarded again, and forwarded several times more. It came to a woman named Karyn, who had just built a brand new barn, who had acres of perfect pasture, who had a daughter with a pony, and who was looking to find a horse for herself and her husband. She’d grown up with gaited horses, and would fully appreciate a Missouri Fox Trotter like Sam. I spoke with Mr. Millman about Karyn. Our conversations were the same as always – namely, me trying to wrangle the indomitable force of nature that was Mr. Millman, with much respect on both sides.

Before Karyn’s visit we talked again, about his hopes, his fears, his expectations about this potential new owner of his beloved horses. I counseled him as best I knew how. He told me, several times, how much he appreciated my help. “Of course,” was all I said. Some duties you do not choose; they choose you.

Karyn came out the next day. The day after that I didn’t hear from either of them. I became nervous. Maybe it hadn’t gone well. I emailed Mr. Millman, who always emailed me back instantaneously. I heard nothing. I called Karyn. She said it went beautifully. She and Mr. Millman had clicked, she said, and she loved the horses. He’d shown her around his house and his property, he had introduced her to the horses. She watched as Mr. Millman said good-bye to Sam. “We’ve come a long way together,” he told Sam. “I will never forget you. I hope you don’t forget me.”

Karyn told Mr. Millman she could pick the horses up on the 12th or the 20th, and Mr. Millman chose the 20th. He couldn’t ride any longer, he said, but he enjoyed coming down to give them a treat. It kept him going. Love, hope, and joy.

As it turns out, what had really kept Mr. Millman going was the knowledge that he needed to find his boys a home before he died. After he met Karyn, he returned to his house, and passed away. The date was November 5th.